Ten years after a law was passed in India, banning doctors from discussing the gender of a fetus with the parents following an ultrasound test, some Indian doctors not only continue to break that law, but even perform abortions if the parents decide to get rid of a female fetus.

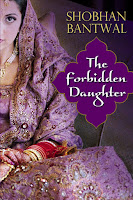

Now, Indian-American author, Shobhan Bantwal, takes us into a world where the corrupt and covert practice of gender-selective abortion still thrives, in her second novel, THE FORBIDDEN DAUGHTER, scheduled for release by Kensington Publishing on August 26, 2008. Her first novel, THE DOWRY BRIDE, dealt with the topic of dowry deaths in India.

THE FORBIDDEN DAUGHTER tells the story of Isha, a young mother who refuses to abort her second child, another girl, despite her in-laws’ dictate to have the abortion. When her husband suddenly becomes the victim of a mysterious murder, she is convinced that her rebellious decision has something to do with it. When Isha leaves her in-laws to raise her daughters on her own, she is faced with the most dangerous battle of her life.

To quote Bantwal about what inspired the book, “After being raised with love and care in India, amidst a family of five girls, it was difficult for me to comprehend that female children are disdained in my country of birth, so much so that female fetuses are aborted without regard for the law, moral values, or even the delicate balance of nature. I felt compelled to write an interesting tale about what could happen if an idealistic woman refused to abort a female child. But I also wanted the story to be one of hope and triumph and the resilience of the human spirit.” However, Bantwal maintains that gender-based abortion is not the norm. “The instances are quite rare when juxtaposed against India’s vast population, but the fact remains that gender-based abortions continue to occur.”

Bantwal weaves the universal themes of love, morality, and courage into a story set against a dramatic and rare backdrop. It brings to light the contradictions of a culture that is both modern and quaintly archaic, a society where women can aspire to the highest elected office and yet be plagued by the dark shadow of female fetus abortion and infanticide.

Many of the cultural elements come from the author’s observations and personal experiences from growing up in a small town in India.

Naazish: What motivates you to pick the topics you do?

Being passionate about women’s rights and women’s issues, I tend to veer towards topics that are dear to my heart. If I can weave a compelling story around a particular theme that has both emotional appeal as well as social/political implications, I feel it gives me an opportunity to both fulfill my creative urge and express my opinion on certain subjects.

Additionally, I find many of my American friends, neighbors, and coworkers have no idea about such issues. Some of them have never even heard of the term “dowry,” or come across a culture that is so male-centric that girls are considered a burden and can be aborted as fetuses and denied the chance to live.

Writing about such topics gives me the perfect opportunity to educate and entertain at the same time. Consequently, my first two books, THE DOWRY BRIDE and THE FORBIDDEN DAUGHTER, deal with hot-button social issues and yet have a romantic story of love, hope and the resilience of the human spirit.

Naazish: What kind of response have you gotten from readers. What's some of the best feedback you've gotten?

Feedback to date has been mixed, and it has been very typical—something that I expected long before my book was published. Most American readers of mainstream women’s fiction with romantic elements seem to love the book. Various book clubs across the country, Canada, and especially in my home state of New Jersey have read the book and continue to do so. I address many of them in person or by phone, and the overall feedback I get is very positive and encouraging. One instructor at a community college made THE DOWRY BRIDE required reading for her course on global cultures and I was thrilled to be invited to address the class.

However, South Asian readers, particularly my fellow Indians, feel that the book is too melodramatic and portrays dowry as an evil custom with no redeeming features. Personally, I find no good qualities in the system as it is practiced today. It probably started out with good intentions, as a way to assure inheritance equity between sons and daughters, but it has deteriorated into something destructive and redundant in a society where women have become economically independent to a large degree.

Some Indians also feel that I have denigrated a particular segment/caste of society by introducing a rape scene where a lower-class man attacks an upper-caste woman. In the book, this incident occurs nearly 60 years ago and the consequences are being felt by the families affected by the act to the present day. I have portrayed that segment from the point of view of an 80-year-old woman (the victim) and it is her prejudices and her bitterness at her attacker that I have put into words. Many readers are offended by this because they feel I have been politically incorrect in my portrayal of the dalit community and that I should be more responsible in my writing. Unfortunately, a writer can never please every reader and I accept that fact.

However, the best feedback has come from one or two e-mailers who have offered me balanced comments—what they liked and what they didn’t, and what they feel would have improved the book. I feel theirs are the most honest commentaries I’ve seen on my book, and perhaps the most useful.

Naazish: What would you say to a potential comment that you're washing dirty laundry in public?

I have read one man’s feedback expressing these exact sentiments. My answer is that the world has a right to know the good and the bad about every culture. It is the only way to make others aware of what goes on in certain cultures and how they could possibly help the innocent victims of certain social customs that continue to be practiced despite laws to ban them. Someone has to speak out on behalf of women who either cannot or do not have the means to request aid. No society is perfect and to write about the negatives or “dirty laundry” is one way of starting a meaningful dialogue on how to eradicate or at least diminish the negatives.

Naazish: Have you always wanted to be a writer or was this something you fell into accidentally?

Although I was a voracious reader all my life, I stumbled into writing at the age of 50. When my husband started working on a project that forced him to stay away from home during weekdays, as an empty-nester, I decided to take up creative writing as a hobby. I started by writing social interest articles for a number of Indian-American publications like India Abroad, Little India, India Currents, DesiJournal.com, and Kanara Saraswat. Then I moved on to short fiction. When my short stories won awards and/or honors in nationwide fiction contests, my ambitions gradually expanded to full-length fiction. I wrote my first novel and it got sold to Kensington Publishing in a two-book contract when I turned 54. I call it my menopausal epiphany.

Naazish: Can you describe the pitching process and how to land an agent?

I wrote very simple query letters to my top-tier of agents. During the first round I received a lot of rejections. So I wrote another book, one set in the U.S., which seemed to elicit plenty of interest from good agents. All of a sudden I got requests from seven agents wanting to see a partial manuscript and four that asked to see the whole book. Eventually three offered me representation and I picked the one that I felt was most suited for my needs. It was also the agency that represents Khaled Hosseini of “The Kite Runner” fame, so I felt the agency would be as asset for me. Sadly that particular manuscript never got sold, but when I asked my agent to look at THE DOWRY BRIDE, she did and she liked it. Luckily it got sold within a few weeks.

Naazish: What advice do you have for other writers?

Other than to keep plugging away and writing what they feel is the right genre for them, I have very little advice for aspiring writers. I took a calculated risk when I started writing Desi romances, which are what I call Bollywood-in-a-book. When I started writing them because I happen to enjoy mainstream fiction with romance as a theme, I never dreamt that a publisher would actually like them, let alone buy them, since most agents and publishers expect serious literary novels from South Asian writers. If a writer enjoys reading and writing a particular genre, they should stick with it. One never knows which publisher is looking for something different.

Naazish: How has life changed now that you're a published author?

Writing has taken over my entire life. I now have two full-time careers (one day job that pays the bills and the other my writing career that makes no money but consumes most of my time). I have no time for anything else lately. One of the risks of taking up writing seriously is the amount of time one needs to invest in it. Marketing the book consumes a very large part of a writer’s life. It is a time and money pit, where the more you pour in, the more it demands. Currently I’m working on a marketing plan for my second book, THE FORBIDDEN DAUGHTER, ready for release on August 26, 2008.

Naazish: Do you have other books in the making?

Yes. Kensington just offered me another two-book contract, so I expect my third book to be released in 2009 and a fourth in 2010, if all goes well and I can produce the stories they are looking for. I love the creative part of being a writer, but I don’t look forward to the marketing end. Overall, it has been a mixed experience—an exhausting yet exciting journey.